Towards sustainable eating: Europe’s path to protein independence

Protein production in Europe stands at the crossroads of several strategic challenges: food security, environmental sustainability, energy efficiency, economic and social resilience. Today, Europe faces a structural dependency on protein imports.

Could a new approach to protein production hold the key to Europe’s food autonomy?

Sustainable food autonomy

The European Union consumes around 71 million tons of raw protein[1] annually to feed its livestock, yet the agricultural capacities permit to produce only 24% of this amount locally. Those proteins (as soy) are imported from South America. This heavy reliance exposes Europe to risks such as price fluctuations related to international markets, geopolitical crisis, and disruptions in supply chains. Recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian war, have highlighted the vulnerability of global supply networks, underscoring the urgent need for the EU to enhance its food sovereignty by investing in more resilient solutions.

The European Union consumes around 71 million tons of raw protein[1] annually to feed its livestock, yet the agricultural capacities permit to produce only 24% of this amount locally. Those proteins (as soy) are imported from South America. This heavy reliance exposes Europe to risks such as price fluctuations related to international markets, geopolitical crisis, and disruptions in supply chains. Recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian war, have highlighted the vulnerability of global supply networks, underscoring the urgent need for the EU to enhance its food sovereignty by investing in more resilient solutions.

Rethinking European agriculture

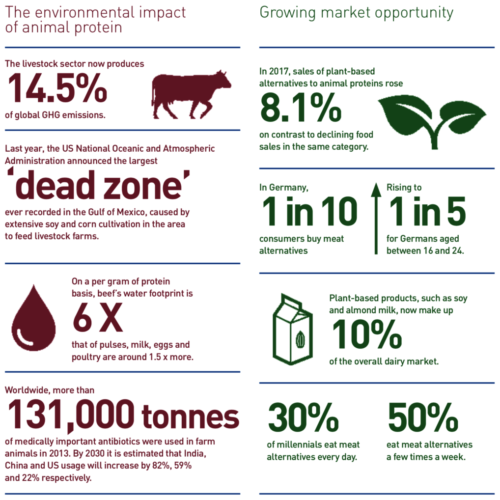

The massive imports of proteins, particularly soy, come at an unsustainable environmental cost. In South America, the expansion of soy monocultures, a major driver of deforestation in the Amazon, devastates unique ecosystems, accelerates biodiversity loss, and exacerbates climate change. More globally, the ecological footprint of meat production is equally concerning: intensive animal production generates massive greenhouse gas emissions, pollutes soils with excess nitrogen, and pushes our ecosystems to the brink.

Energy efficiency and carbon Footprint reduction

Animal protein production, especially beef, is among the most energy-intensive and carbon-heavy agricultural practices. In fact, it now accounts for 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, more than the transport sector and places a heavy burden on the agricultural climate balance. Adding to this is the production of grains and soy for livestock feed, which requires enormous amounts of energy not only for cultivation but also for transporting raw materials across the globe.

Health and well-being

Diet plays a crucial role in this transformation. In Europe, the consumption of animal proteins far exceeds recommended levels, leading to adverse public health consequences, including an increase in cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. Paradoxically, the consumption of plant proteins has declined in recent decades, despite their well-documented health benefits.

Towards sustainable eating: blending plant-based alternatives and protein innovation in Europe

As Europe embarks on a quest to renew its model of protein production and consumption, plant-based proteins — such as peas, lentils, and soy — are emerging as both a sustainable and promising solution for the future. Less demanding in terms of land, water, and energy than their animal counterparts, these proteins stand out for their ability to generate significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions. Their integration into our diets is not just a trend; it is positioned as an essential strategy for mitigating the carbon footprint of the European food system.

As Europe embarks on a quest to renew its model of protein production and consumption, plant-based proteins — such as peas, lentils, and soy — are emerging as both a sustainable and promising solution for the future. Less demanding in terms of land, water, and energy than their animal counterparts, these proteins stand out for their ability to generate significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions. Their integration into our diets is not just a trend; it is positioned as an essential strategy for mitigating the carbon footprint of the European food system.

Economic and social potential of plant proteins

From an economic perspective, the development of plant protein crops presents a outstanding opportunity for the European market: by intensifying investments in research and innovation, the EU can not only support the local production of protein crops but also invigorate the agricultural sector. This strategy could further bolster the agri-food industry and create local jobs. Moreover, it encourages healthier plant-based diets, thereby reducing public health costs associated with excessive red meat consumption.

Socially, the transition towards a diet focused more on plant proteins addresses consumers’ growing concerns about health, animal welfare, and sustainability. This shift in dietary habits and societal values reflects a heightened awareness among citizens, prompting them to consider more balanced and sustainable dietary choices.

Faced with increasing challenges related to food security, public health, and the environment, can Europe genuinely consider a transition towards alternatives to animal proteins that blend sustainability and innovation?

While the European Union does not suffer from a protein shortage, alternatives to conventional animal proteins are gaining importance in addressing health, nutrition, and sustainability challenges. These alternatives fall into three main categories:

- Plant-Based alternatives: Proteins derived from plants, designed to replace animal proteins.

- Alternative proteins: It includes ingredients well-established in other regions of the world, such as algae and insects, that are just beginning to make their way into Europe. It also includes proteins generated by microbial fermentation, as Yusto and SylPro.

- Cultured of cultivated meat: Emerging from recent innovations, these include meat grown in a laboratory with stem cells from animals —an ethical and technological revolution in the food landscape.

[1] European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Hristov, J., Tassinari, G., Himics, M., Beber, C., Barbosa, A., Isbasoiu, A., Klinnert, A., Kremmydas, D., Tillie, P., & Fellmann, T. (2024). Closing the EU protein gap – drivers, synergies, and trade-offs. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/84255, JRC137180.